Tuesday, December 30, 2008

Sunday, December 28, 2008

A photograph, footprints

Here is a joke, courtesy of Groucho Marx, when

asked to show his identity card: “Sorry, I do

not have a photograph. But you can have my

footprints. They are upstairs in my socks.”

A photograph, footprints.

The first is a clear case of self-manifestation.

Yet, what is often forgotten: a photograph is

the fruit of man’s demand for visualization, a

demand that has been around for thousands of

years, which began to broaden since the days

of Plato. We live in an oculocentric culture:

we almost fully equate the “known” with the

“visible” and thus all things related to the eye

crowd in to fill language …

Granted, an oculocentric culture has ushered

in a remarkable plethora of visual technology.

Yet in all that there is a history of power that

cannot be dismissed – that is, when space is read

as a map, the Divine World as Holy Book and

darkness as a flaw, As Derrida says: “There is a

sacred and ancient friendship between light

and power.”

A photograph is the result of an aggressive

process; they use, after all, the words “shooting”

and “shot.” As an identity marker, a photograph

is validated by the very power that created

the symbolic order – language, laws, customs,

the state. It is fixed and framed by that order.

“Look, a Negro!” cried a little girl on a street of

Paris, pointing at Franz Fanon. At that instant,

Fanon knew he did not decide who he was.

It is for that reason Groucho Marx’s utterance,

spoken in jest, is, in fact, a resistance. He did

not place the photograph in a defining position.

He pointed, instead, to the second element in

our dichotomy: footprints in socks …

Traces of passage, signs with multiple

meanings, something that may be wiped clean

tomorrow by a new journey …

Goenawan Mohamad

- On God and Other Unfinished Things (pp157-8)

Wednesday, December 10, 2008

camera-shy

I bought my first digital camera in Jakarta in 2004, a Canon G5, with money I got from a job making photos for Metro Department Store. Thousands of photos later this camera was stolen on a vacation in Barcalona in 2008. I have replaced the G5 with the upgraded G9. The photo above was taken in Bali in 2005, my camera-shy Mei.

Saturday, November 29, 2008

Thursday, November 27, 2008

Spatial Justice

Justice is something

that is because of its absence.

[...]

It is an absence that pleads;

its mark the searing wound

that takes place

when injustice pervades

space.

Goenawan Mohamad

- On God and Other Unfinished Things (p147)

that is because of its absence.

[...]

It is an absence that pleads;

its mark the searing wound

that takes place

when injustice pervades

space.

Goenawan Mohamad

- On God and Other Unfinished Things (p147)

Thursday, November 13, 2008

Life & Death: for the Love of God

It is the Platonic ideal to turn away from mortality, vulnerability, contingency, and mutability of the worldly appearances and to search for unchanging stability, clarity, and preciseness. It is a move away from the plural to the singular.

Reading, writing, thinking and talking about our vulnerability, though, does not make us any less vulnerable. However, it can give us ways to create lasting values despite our mortality. Recognizing the contingency of our horizons means that we can have the power to alter them.

All moral systems start by the acknowledgement that life of us finite beings itself ought to be an inherent value. Life itself is our source of values, without a life no values. If we do not value life in all its facets then we cannot create values. If life is not seen as the starting value one is not immoral – that means that one breaks the norms and values of a moral system – but amoral – that means that one goes beyond morality, i.e. nihilism, a leap into the void of nothingness.

An example of this nihilism can be seen in the movie ‘Funny Games’ by the Austrian Michael Haneke (1997, 2008 remake by the same author). In this movie people are murdered for no reason whatsoever. Haneke is critical of violence in such movies as ‘Pulp Fiction’ by Quentin Tarantino (1994). Tarantino does not give any reason for the use of violence other than entertainment value.

Another example is Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s book ‘Crime and Punishment’. The main character of this book is Raskalnikov and he commits a murder to see if he can get away with it without feeling guilty. According to Raskalnikov, men like Napoleon Bonaparte are great because they can step over petty conventional morality. Raskalnikov, though, is no Napoleon, he has to deal with his internal struggle and he is punished by the conscience he tried to escape from in the first place.

If we keep Ludwig Wittgenstein’s adagio in mind that an aesthetic form or style shows an ethical perspective on the world, then how should we judge the actions of individuals in general and creations of artists in particular? A different moral perspective needs to be shown through a different form or style. How then should we judge the art work ‘For the Love of God’ (2007) by the British artist Damien Hirst? What does it all come to? What sense does it have or give? The use of a form or style without the will to show a perspective on one’s world is nihilistic.

‘For the Love of God’ is a platinum crust of a human skull of the eighteenth century, which Hirst bought at an antique shop. The skull is encrusted with 8,601 flawless diamonds, with which Hirst messed-up the global diamond market. Set on the forehead is a large, pear-shaped diamond, which is called the ‘Skull Star Diamond’. And the teeth are from the original skull.

Damien Hirst says in an interview (in ‘Oog’, Rijksmuseum magazine for art and history, no.4, 11-9-2008): “As an artist I try to make things that people can believe in, that they can relate to, that they can experience. You therefore have to show them as well ass possible.” An art work that is skillfully crafted can become immortal.

Dutch art historian Rudi Fuchs described ‘For the Love of God’ as ‘a supernatural skull, almost heavenly’. Fuchs relates the work to the ‘memento mori’ theme, which was popular in the Dutch Golden Age of the seventeenth century. Hirst selected a series of old paintings owned by the Rijksmuseum to be shown together with his work at this museum in Amsterdam.

Hirst explores human experiences: life, death, truth, love, immortality, money and art. The traditional ‘memento mori’ theme addresses the transience of human existence. Hirst says: “I am aware of mental contradictions in everything: I am going to die and I want to live for ever. I can’t escape the fact and I can’t let go of the desire.” ‘For the Love of God’ is therefore also a self-portrait. Hirst asked himself what the maximum is that can be thrown at death. Diamonds!

Hirst, obviously, employs irony. This irony can already be identified in the title. Irony is a way of dealing with contradictions. The danger of irony is that we can never know for sure what is meant. Or worse: total misunderstanding. Some call Hirst’s art vulgar and cheap (of course in a metaphorical sense, because those 8,601 diamonds are worth a fortune, the production was a stunning fourteen million British Pounds).

How to deal with disagreement, indeterminacy, inconsistency, incoherence, incongruity, ambivalence, heterogeneity, opacity, paradoxy, and uncertainty in our present-day modernity? Irony is one way, however, sometimes it can be misleading as well. Friedrich Nietzsche is the philosopher that warned us that ontological uncertainty causes anxiety, and possibly violence against the ‘stranger’, against what is ‘alien’. According to Zygmunt Bauman the task of philosophy today is to teach us how to deal with uncertainty and contingency. The search for absolute and universal values, though, is the existential need for traditional security.

The debates concerning abortion, euthanasia, and the death penalty seem to show that we do not have a consensus on the question what constitutes man.

It is interesting to note that orthodox believers, who claim to believe in the sanctity of life, are against euthanasia and abortion (i.e. they claim to be pro-life) but they are not against the death penalty. They rather see man going to war then that they make love (i.e. homosexuality).

We can also apply the Wittgensteinian aesthetic ethics/ethical aesthetics on fundamentalists in general and terrorists in particular. Through what symbolic forms do they convey meaning?

According to the sociologist Julia Suryakusuma Islamist parties, like PKS, and organizations, like MUI and FPI, promote the prudish anti-pornography bill because in paradise lusty hookers await. In our mundane world the libido needs to be regulated. It is better to go to war – Jihad! – than to make love.

For the self-acclaimed martyrs await lusty hookers in paradise. They withdraw themselves from life – taking others, infidel bystanders, with them. Are these martyrs Dostoyevsky’s modern-day nihilists? They claim to know the exact ways of Allah even though the infinite is mysterious to us finite beings. Isn’t that more blasphemous that a cartoon of a Danish kafir who depicted the prophet as a terrorist?

Susan Sontag writes provocatively that the 9/11 terrorists are no cowards (‘Talk of the Town’ in ‘The New Yorker’, 24-9-2001). She writes: “Where is the acknowledgement that this was not a ‘cowardly’ attack on ‘civilization’ or ‘liberty’ or ‘humanity’ or ‘the free world’ but an attack on the world’s self-proclaimed superpower, undertaken as a consequence of specific American alliances and actions? […] In the matter of courage (a neutral virtue): Whatever may be said of the perpetrators […], they were not cowards.”

It is questionable whether courage is a neutral virtue. Aristotle claims in the ‘Nicomachean Ethics’ that the deficiency of courage is cowardice and that the excess is rashness, i.e. a display of too much courage at the wrong place in the wrong time directed to the wrong people using the wrong means (bombs instead of words).

It is also problematic that Sontag puts the responsibility of the attack on the side of the American people working in those WTC towers; those Americans did not do this to themselves. Buruma and Margalit write in ‘Occidentalism, The West in the Eyes of its Enemies’: “anti-Americanism is sometimes the result of specific American policies […]. But whatever the U.S. government does or does not do is often beside the point. [… Occidentalism refers] not to American policies, but to the idea of America itself, as a rootless, cosmopolitan, superficial, trivial, materialistic, racially-mixed, fashion-addicted civilization.”

Terrorism and the war-on-terror kill the most precious value – life – by creating death and fear.

Amrozi showed a smile and thumbs-up when he heard the verdict for his part in the 2002 Bali-bombings. Amrozi views himself as a martyr; he dies for a just cause he claims. For him killing was an act of justice. For him those people are not innocent. He does not suffer from his conscience for he is convinced to have an entry ticket to paradise.

The survivors get a taste of revenge. The Indonesian justice system provides retaliation. Perhaps the death penalty is like a placebo that works for those who lost loved ones.

To view Amrozi as less than human, though, insults the court; he could have been killed right away. Is a world without the likes of Amrozi a safer place? No, I am afraid not. To make our place safer we need more than a tighter legal and security system. We need to know the soil of the Amrozis. And the Indonesian authorities postponed the execution for fear of the Muslim voice – for fear of the soil where the Amrozis are born. Moreover, Amrozi was turned in a celebrity due to heavy media exposure.

Is terrorism a form of art as a leap in imagination as some claim? No! Terrorists dehumanize. Terrorists take precious lives. And artists, when their work succeeds, create something immortal. Immortality is the wish to live forever in this imperfect world. And this immortality is not to be understood in the Platonic sense. Plato and terrorists yearn for eternity, i.e. for never having lived at all by leaping from an earthly life to the eternal life. For them life is punishment, not death, that is the reason why Amrozi smiled...

Also published in the Jakarta Globe, see here.

Reading, writing, thinking and talking about our vulnerability, though, does not make us any less vulnerable. However, it can give us ways to create lasting values despite our mortality. Recognizing the contingency of our horizons means that we can have the power to alter them.

All moral systems start by the acknowledgement that life of us finite beings itself ought to be an inherent value. Life itself is our source of values, without a life no values. If we do not value life in all its facets then we cannot create values. If life is not seen as the starting value one is not immoral – that means that one breaks the norms and values of a moral system – but amoral – that means that one goes beyond morality, i.e. nihilism, a leap into the void of nothingness.

An example of this nihilism can be seen in the movie ‘Funny Games’ by the Austrian Michael Haneke (1997, 2008 remake by the same author). In this movie people are murdered for no reason whatsoever. Haneke is critical of violence in such movies as ‘Pulp Fiction’ by Quentin Tarantino (1994). Tarantino does not give any reason for the use of violence other than entertainment value.

Another example is Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s book ‘Crime and Punishment’. The main character of this book is Raskalnikov and he commits a murder to see if he can get away with it without feeling guilty. According to Raskalnikov, men like Napoleon Bonaparte are great because they can step over petty conventional morality. Raskalnikov, though, is no Napoleon, he has to deal with his internal struggle and he is punished by the conscience he tried to escape from in the first place.

If we keep Ludwig Wittgenstein’s adagio in mind that an aesthetic form or style shows an ethical perspective on the world, then how should we judge the actions of individuals in general and creations of artists in particular? A different moral perspective needs to be shown through a different form or style. How then should we judge the art work ‘For the Love of God’ (2007) by the British artist Damien Hirst? What does it all come to? What sense does it have or give? The use of a form or style without the will to show a perspective on one’s world is nihilistic.

‘For the Love of God’ is a platinum crust of a human skull of the eighteenth century, which Hirst bought at an antique shop. The skull is encrusted with 8,601 flawless diamonds, with which Hirst messed-up the global diamond market. Set on the forehead is a large, pear-shaped diamond, which is called the ‘Skull Star Diamond’. And the teeth are from the original skull.

Damien Hirst says in an interview (in ‘Oog’, Rijksmuseum magazine for art and history, no.4, 11-9-2008): “As an artist I try to make things that people can believe in, that they can relate to, that they can experience. You therefore have to show them as well ass possible.” An art work that is skillfully crafted can become immortal.

Dutch art historian Rudi Fuchs described ‘For the Love of God’ as ‘a supernatural skull, almost heavenly’. Fuchs relates the work to the ‘memento mori’ theme, which was popular in the Dutch Golden Age of the seventeenth century. Hirst selected a series of old paintings owned by the Rijksmuseum to be shown together with his work at this museum in Amsterdam.

Hirst explores human experiences: life, death, truth, love, immortality, money and art. The traditional ‘memento mori’ theme addresses the transience of human existence. Hirst says: “I am aware of mental contradictions in everything: I am going to die and I want to live for ever. I can’t escape the fact and I can’t let go of the desire.” ‘For the Love of God’ is therefore also a self-portrait. Hirst asked himself what the maximum is that can be thrown at death. Diamonds!

Hirst, obviously, employs irony. This irony can already be identified in the title. Irony is a way of dealing with contradictions. The danger of irony is that we can never know for sure what is meant. Or worse: total misunderstanding. Some call Hirst’s art vulgar and cheap (of course in a metaphorical sense, because those 8,601 diamonds are worth a fortune, the production was a stunning fourteen million British Pounds).

How to deal with disagreement, indeterminacy, inconsistency, incoherence, incongruity, ambivalence, heterogeneity, opacity, paradoxy, and uncertainty in our present-day modernity? Irony is one way, however, sometimes it can be misleading as well. Friedrich Nietzsche is the philosopher that warned us that ontological uncertainty causes anxiety, and possibly violence against the ‘stranger’, against what is ‘alien’. According to Zygmunt Bauman the task of philosophy today is to teach us how to deal with uncertainty and contingency. The search for absolute and universal values, though, is the existential need for traditional security.

The debates concerning abortion, euthanasia, and the death penalty seem to show that we do not have a consensus on the question what constitutes man.

It is interesting to note that orthodox believers, who claim to believe in the sanctity of life, are against euthanasia and abortion (i.e. they claim to be pro-life) but they are not against the death penalty. They rather see man going to war then that they make love (i.e. homosexuality).

We can also apply the Wittgensteinian aesthetic ethics/ethical aesthetics on fundamentalists in general and terrorists in particular. Through what symbolic forms do they convey meaning?

According to the sociologist Julia Suryakusuma Islamist parties, like PKS, and organizations, like MUI and FPI, promote the prudish anti-pornography bill because in paradise lusty hookers await. In our mundane world the libido needs to be regulated. It is better to go to war – Jihad! – than to make love.

For the self-acclaimed martyrs await lusty hookers in paradise. They withdraw themselves from life – taking others, infidel bystanders, with them. Are these martyrs Dostoyevsky’s modern-day nihilists? They claim to know the exact ways of Allah even though the infinite is mysterious to us finite beings. Isn’t that more blasphemous that a cartoon of a Danish kafir who depicted the prophet as a terrorist?

Susan Sontag writes provocatively that the 9/11 terrorists are no cowards (‘Talk of the Town’ in ‘The New Yorker’, 24-9-2001). She writes: “Where is the acknowledgement that this was not a ‘cowardly’ attack on ‘civilization’ or ‘liberty’ or ‘humanity’ or ‘the free world’ but an attack on the world’s self-proclaimed superpower, undertaken as a consequence of specific American alliances and actions? […] In the matter of courage (a neutral virtue): Whatever may be said of the perpetrators […], they were not cowards.”

It is questionable whether courage is a neutral virtue. Aristotle claims in the ‘Nicomachean Ethics’ that the deficiency of courage is cowardice and that the excess is rashness, i.e. a display of too much courage at the wrong place in the wrong time directed to the wrong people using the wrong means (bombs instead of words).

It is also problematic that Sontag puts the responsibility of the attack on the side of the American people working in those WTC towers; those Americans did not do this to themselves. Buruma and Margalit write in ‘Occidentalism, The West in the Eyes of its Enemies’: “anti-Americanism is sometimes the result of specific American policies […]. But whatever the U.S. government does or does not do is often beside the point. [… Occidentalism refers] not to American policies, but to the idea of America itself, as a rootless, cosmopolitan, superficial, trivial, materialistic, racially-mixed, fashion-addicted civilization.”

Terrorism and the war-on-terror kill the most precious value – life – by creating death and fear.

Amrozi showed a smile and thumbs-up when he heard the verdict for his part in the 2002 Bali-bombings. Amrozi views himself as a martyr; he dies for a just cause he claims. For him killing was an act of justice. For him those people are not innocent. He does not suffer from his conscience for he is convinced to have an entry ticket to paradise.

The survivors get a taste of revenge. The Indonesian justice system provides retaliation. Perhaps the death penalty is like a placebo that works for those who lost loved ones.

To view Amrozi as less than human, though, insults the court; he could have been killed right away. Is a world without the likes of Amrozi a safer place? No, I am afraid not. To make our place safer we need more than a tighter legal and security system. We need to know the soil of the Amrozis. And the Indonesian authorities postponed the execution for fear of the Muslim voice – for fear of the soil where the Amrozis are born. Moreover, Amrozi was turned in a celebrity due to heavy media exposure.

Is terrorism a form of art as a leap in imagination as some claim? No! Terrorists dehumanize. Terrorists take precious lives. And artists, when their work succeeds, create something immortal. Immortality is the wish to live forever in this imperfect world. And this immortality is not to be understood in the Platonic sense. Plato and terrorists yearn for eternity, i.e. for never having lived at all by leaping from an earthly life to the eternal life. For them life is punishment, not death, that is the reason why Amrozi smiled...

Also published in the Jakarta Globe, see here.

Friday, October 24, 2008

98-08

Tuesday 28 October at 3 o'clock a selection of short movies will be screened at the Faculty of Philosophy, Parahyangan University, Jl.Nias2 (lantai2). The Indonesion cineasts question the meaning of 1998 today. After the screening there will be time for discussion. For more info: http://9808films.wordpress.com/.

Sunday, October 19, 2008

ROSA

Rosa Verhoeve is a Dutch photographer who won the prestigious Zilveren Camera in 2005. She gave a workshop at Parahyangan University, Bandung. For more info on her work see here and here. I am very happy to say that Rosa and me are going to exchange photographs!

Monday, October 13, 2008

Sunday, October 5, 2008

The moral power of James Nachtwey's photos

James Nachtwey was awarded the TED prize in 2007 that came with 100,000 US dollar. Nachtwey uses this money to create awareness for the forgotten plague TB. He says: "I have been a witness, and these pictures are my testimony. The events I have recorded should not be forgotten and must not be repeated."

Thursday, October 2, 2008

Gus Dur

Former president and leader of the largest Muslim organization Nahdatul Ulama (NU) K.H. Abdurraman Wahid who is better known as Gus Dur (born 7 September, 1940) likes to joke around (see here): "President Abdurrahman Wahid jokes that while Sukarno was crazy about women; his successor, Suharto, was crazy about money; and the third president, BJ Habibie, was just plain crazy - in his own case he says it was those who elected him who were the crazy ones." His presidency only lasted from 1999 to 2001 when he was impeached on grounds of corruption allegations for which he was never tried and sentenced. It is unlikely that he will be reelected in the presidential elections of 2009. (See also the Wahid Institute.)

Monday, September 29, 2008

(de-)construction

The Agung Podomoro Group - allegedly headed by Tomy Winata - is building Central Park Residences, of which Mediterania Garden Residences 2 at Tanjung Duren Raya, West Jakarta, is a part. I was not allowed to take this picture and a security guard sent me away. This construction site is supposed to be a green area so that it could have functioned as a water catching area. The hinterland of this site is prone to floods during the rain season, up to two meters, and most likely this mega construction is not making matters any better. I took this picture because I think it is ironic if a lack of green is covered-up by a photo of trees on a building.

Saturday, September 27, 2008

urban anxiety

Peter Nas and Pratiwo write: “uncertainty has become a certainty […].”[1] The gated communities in suburbia symbolize the fear of the stranger, where homogeneity symbolizes the need for security. Nas and Pratiwo call this the ‘architecture of fear’.[2] The walls, gates, barbed wire and guards symbolize the graving for security while not providing real safety. Abidin Kusno comments: “They [the fences] no longer seem to connote power. They do not have any real power to exclude. Rather, these enclosures signify defense, fear, and abandonment. They keep things inside […].”[3]

[1] See p289, Nas, P.J.M., Pratiwo, ‘The streets of Jakarta, Fear, trust and amnesia in urban development’, in: Nas, P.J.M., Persoon, G., and Jaffe, R. (eds.), Framing Indonesian realities: Essays in symbolic anthropology in honour of Reimar Schefold, Leiden: KITLV Press, 2003.

[2] See p292, idem.

[3] See p176, Kusno, A., ‘Remembering/Forgetting the May Riots: Architecture, Violence, and the Making of ‘Chinese Cultures’ in Post-1998 Jakarta’, in: Public Culture, Vol.15, no.1 (2003): pp149-177.

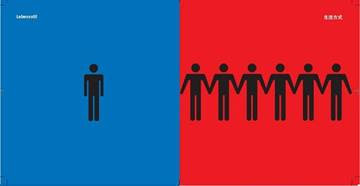

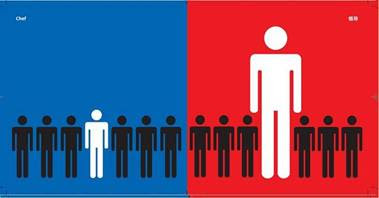

hilarious prejudices

Blue are the Westerners and red are the Asians; a playful way of making fun of prejudices. However, as Edward Said writes in 'Orientalism' (p4-5): "the Orient is not an inner fact of nature. It is not merely there, just as the Occident itself is not there either [...] - such locales, regions, geographical sectors as 'Orient' and 'Occident' are man-made."

Thursday, September 18, 2008

PP

In the second banner from the left Pemuda Pancasila wishes success to newly elect mayor of Bandung, Dada. Pemuda Pancasila advertises itself as a youth organization, but by most it is viewed as a government backed group of thugs or a para militairy organization. Why does the mayor want to have this public show of support?

Monday, September 15, 2008

Grounded

Adam Air has grounded itself after another of its planes crashed. The EU has decided to ban Indonesian airline companies of entering its airspace because their planes have proven to be too often in a fatal state. The Indonesian elite has responded in a nationalistic way, it is seen as a form of neo-colonialism.

Tuesday, September 2, 2008

Sunday, August 24, 2008

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)